After more than 30 years of making black music for black people, Malaco Records defines the state of contemporary southern rhythm and blues, soul, and gospel.

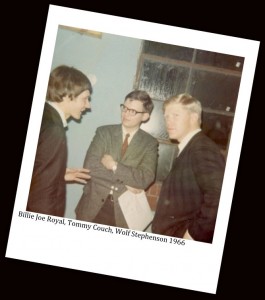

“The Last Soul Company” started as a pocket-change enterprise in the early 1960s with college students Tommy Couch and Wolf Stephenson booking bands for fraternity dances at the University of Mississippi.

After graduation, Tommy Couch opened shop in Jackson, Mississippi as Malaco Attractions with brother-in-law Mitchell Malouf (Malouf + Couch = Malaco). Wolf Stephenson joined them in promoting concerts by Herman’s Hermits, the Who, the Animals, and others.

In 1967 the company opened a recording studio in a building that remains the home of Malaco Records.  Experimenting with local songwriters and artists, the company began producing master recordings. Malaco needed to license their early recordings with established labels for national distribution. Between 1968 and 1970, Capitol Records released six singles and a Grammy-nominated album by legendary bluesman Mississippi Fred McDowell. Deals for other artists were concluded with ABC, Mercury, and Bang.

Experimenting with local songwriters and artists, the company began producing master recordings. Malaco needed to license their early recordings with established labels for national distribution. Between 1968 and 1970, Capitol Records released six singles and a Grammy-nominated album by legendary bluesman Mississippi Fred McDowell. Deals for other artists were concluded with ABC, Mercury, and Bang.

Revenue from record releases was minimal, however, and Malaco survived doing jingles, booking bands, promoting concerts, and renting the studio for custom projects.

In May 1970, a bespectacled producer-arranger changed the struggling company’s fortune. Wardell Quezergue made his mark with New Orleans stalwarts Fats Domino, Professor Longhair, and others. He offered to supply Malaco with artists in return for studio time and session musicians. With very little money left, Malaco knew this might be their last shot at making something happen.

Wardell brought five artists to Jackson in a borrowed school bus for a marathon session that yielded two mega-hits – King Floyd’s “Groove Me” and Jean Knight’s “Mr. Big Stuff.” But the tracks met rejection when submitted to Stax and Atlantic Records for distribution. Frustrated, Malaco released the King Floyd tracks on its own Chimneyville label. When “Groove Me” started a wildfire of radio play and sales, Atlantic picked the record up for distribution after all, giving Malaco a label deal for future Chimneyville product. “Groove Me” entered the national charts in October, going to #1 R&B and #6 pop. In 1971, Chimneyville scored again with King Floyd’s “Baby Let Me Kiss You” (#5 R&B and #29 Pop). Meanwhile, Stax decided to take a chance on “Mr. Big Stuff,” selling over two million copies on the way to #1 on the R&B charts and #2 pop.

Wardell brought five artists to Jackson in a borrowed school bus for a marathon session that yielded two mega-hits – King Floyd’s “Groove Me” and Jean Knight’s “Mr. Big Stuff.” But the tracks met rejection when submitted to Stax and Atlantic Records for distribution. Frustrated, Malaco released the King Floyd tracks on its own Chimneyville label. When “Groove Me” started a wildfire of radio play and sales, Atlantic picked the record up for distribution after all, giving Malaco a label deal for future Chimneyville product. “Groove Me” entered the national charts in October, going to #1 R&B and #6 pop. In 1971, Chimneyville scored again with King Floyd’s “Baby Let Me Kiss You” (#5 R&B and #29 Pop). Meanwhile, Stax decided to take a chance on “Mr. Big Stuff,” selling over two million copies on the way to #1 on the R&B charts and #2 pop.

Malaco’s studio and session musicians were now in demand. Atlantic sent the Pointer Sisters among others for the Malaco touch; Stax sent Rufus Thomas and others. And, in January 1973, Paul Simon recorded material for his There Goes Rhymin’ Simon album.

Later that year, Malaco released its first gospel record, “Gospel Train” by the Golden Nuggets. Also in 1973, King Floyd’s “Woman Don’t Go Astray” made #5 R&B.

By 1974, however, studio bookings were down to a trickle, Atlantic had dropped their distribution option, King Floyd had become difficult to work with, and Wardell Quezergue had lost his magic touch. As cash flow dried up, a disenchanted Mitchell Malouf left the company.

When Dorothy Moore recorded “Misty Blue” in 1973, Malaco got stacks of rejection slips trying to shop the master to other labels. Now, in 1975, Malaco was broke and desperate for something to sell. With just enough cash to press and mail out the record, “Misty Blue” was released on the Malaco label just before Thanksgiving. Luckily, it took off the moment it hit radio turntables.

“Misty Blue” earned gold records around the world, peaking at #2 R&B and #3 pop in the USA, and #5 in England. This was followed by thirteen chart records and five Grammy nominations for Moore by 1980.

Another Malaco gamble in late 1975 was targeting the gospel market again with the Jackson Southernaires. The gamble paid off, and other premium gospel artists signed on, including the Soul Stirrers, The Sensational Nightingales, The Williams Brothers, The Truthettes, and The Angelic Gospel Singers, to name a few. The Southernaires’s Frank Williams became Malaco’s Director of Gospel Operations, producing virtually every Malaco gospel release until his untimely death in 1993.

By 1977, songwriters, artists, and producers from the defunct Stax Records were knocking on Malaco’s doors, including Eddie Floyd, Frederick Knight, the Fiestas, and David Porter. Other Malaco signings included McKinley Mitchell.

Stewart Madison also joined the company during this time as a partner, assuming much of the business management functions while Wolf and Tommy concentrated on the creative end.

Malaco made several attempts at the disco market, but its main contribution to the era was providing the studio and session musicians for Anita Ward’s “Ring My Bell.”

Frederick Knight produced “Ring My Bell” for his own Juana label, which, like Malaco, was distributed by T.K. Records in Miami. In the summer of 1979 “Ring My Bell” was omnipresent, going to #1 on both Pop and R&B charts, and selling an estimated 10 million copies worldwide.

A key player working “Ring My Bell” was T.K.’s venerable promotion man, Dave Clark. Then in his seventies, Clark was the undisputed dean of promotion men. He also broke a Malaco track called “Get Up and Dance” by Freedom on New York’s club scene in 1979. Starting with Grandmaster Flash, the track became one of the most sampled records of all-time.

Also hot that summer, Fern Kinney’s electronic remake of “Groove Me” entered the R&B and disco charts in August. The follow-up, “Together We Are Beautiful,” reached #1 on British pop charts in 1980.

Malaco relied greatly on Dave Clark’s promotional efforts at T.K. So when T.K. shuttered in 1980, Malaco hired Clark. His unrivaled access to radio and credibility with artists soon paid off with his recruitment of Z.Z. Hill.

Malaco now stopped trying to compete with mainstream labels. It fell back on what it did so well – down home black music. Larger labels dismissed the genre as an unprofitable relic of the past. However, Malaco could make a tidy profit selling 25,000 – 50,000 units. Starting with Z.Z Hill, Malaco became the center of the universe for old-time blues and soul.

Since blues supposedly no longer sold, everyone was shocked when Hill’s second album, Down Home Blues, sold 500,000 copies. It was the most successful blues album ever, revealing a core audience for quality blues records. It also became an anthem for R&B singers struggling against disco and the emergence of rap.

Denise LaSalle charted fourteen times in the 1970s. But during the disco era, her R&B style was called blues, and big labels were no longer interested. At Dave Clark’s suggestion, she wrote “Someone Else is Steppin In” for Z.Z. Hill.

It was a southern blues-radio staple and racked up substantial sales, but never showed up on national charts. This became the rule. Malaco’s undisputed sales successes could never be measured by Billboard chart positions during the 1980s.

Like Denise LaSalle, Benny Latimore’s 13 R&B chart hits of the 1970s were meaningless by 1981 when Dave Clark steered him to Malaco. And Denise resurrected her artist’s career at Malaco, starting in 1983 with an album called Lady in the Street.

By now, Malaco had found its niche and was the dominant southern R&B label in the country. It also developed an identifiable sound via a core group of session musicians and songwriters.

The house band was anchored by Carson Whitsett on keyboards, Larry Addison on second keyboard; James Robertson on drums, Ray Griffin on bass, and Dino Zimmerman on guitar. A steady stream of strong material flowed from key songwriters such as George Jackson, Larry Addison, Rich Cason, and Jimmy Lewis.

After 29 chart entries for other labels, blues guitarist Little Milton Campbell signed with Malaco in 1984. Little Milton’s first Malaco single “The Blues is Alright” reestablished his presence as a major blues artist and solidified Malaco’s reputation as the contemporary southern blues company.

Z.Z. Hill had become a blues superstar when he suddenly passed away in 1984. His funeral was attended by a who’s who of southern blues culture. Hearing Johnnie Taylor sing at the service, Tommy Couch invited Taylor to become Malaco’s new flagship artist.

Johnnie had earned 20 hits starting in 1968. But, like other future Malaco’s artists, he was considered a relic by mainstream labels in 1984.

Despite the soulful grooves generated by Malaco’s stars in the 1980s, they were pigeonholed as blues artists by radio programmers and trade journals. In the 1970s, mainstream stars like Denise LaSalle, Latimore, Little Milton and, especially, Johnnie Taylor, sold 500,000+ copies of their hits. Now, they were consigned to the industry margins, selling 100,000 units at best.

Soul was reclassified as blues because of an aging demographic. To most radio programmers, older black people listened to the blues. So, when Johnnie Taylor’s fans grew older, he was a “blues artist.” The music hadn’t changed, but the way it was understood, marketed, and consumed had shifted significantly.

In 1985 Malaco signed Bobby Blue Bland. The blues legend had notched up 62 Billboard R&B chart records in 25 years, though few of them made an impression on pop radio.

That summer, Tommy Couch, Wolf Stephenson and Stewart Madison purchased the Muscle Shoals Sound Studio, label, and publishing company. The studio and its fabled rhythm section (Jimmy Johnson, David Hood, Roger Hawkins, and Barry Beckett) are credited with gold records by the Staple Singers, Paul Simon, Aretha Franklin, Bob Seger, Rod Stewart, and Wilson Pickett, to name a few. Even more valuable was their publishing company containing moneymakers like “Old Time Rock and Roll” and “Torn Between Two Lovers.”

Clearly the dominant contemporary southern blues label, Malaco purchased the gospel division of Savoy Records in 1986. Now it was also the preeminent black gospel company in North America. The Savoy acquisition brought a vast catalog of classic recordings dating back decades, including albums by Shirley Caesar, Rev. James Cleveland, Albertina Walker, The Caravans, Inez Andrews, The Georgia Mass Choir, and The Florida Mass Choir. In further expansion moves that year, Malaco entered the world of telemarketing.

1989 saw the Malaco debut of Former Stax star Shirley Brown, and Bobby Blue Bland’s Midnight Run LP remained on Billboard’s Top Black album charts for more than 52 weeks. But this was also the year Dave Clark finally came off the road.

Clark often softened up program directors, saying the current record he was working was his very last. At Malaco he had at least a dozen “last records,” claiming he was retiring or dying or too old to be on the road anymore. Malaco hired Clark a driver, but had to pull him off the road entirely in 1989. Thereafter, he was driven to the office occasionally to hang out, hold court, and doze off, finally passing away in 1995.

As Clark retired, a new generation prepared to become part of Malaco’s future. Born in 1965, Tommy Couch Jr. followed his father’s footsteps, starting a booking agency to mine fraternity bookings on southern campuses.

After earning a marketing degree, Couch Jr. started Waldoxy Records to focus on alternative rock and white blues bands. This marketing strategy had mixed results. After issuing a successful anthology of McKinley Mitchell’s Malaco recordings, Waldoxy’s next signing was blues comedian Joe Poonanny.

From now on, Waldoxy targeted the same southern soul/blues market that traditionally supported Malaco, signing Bobby Rush, Artie “Blues Boy” White, and others. The difference, according to Tommy Jr., is that Waldoxy has hotter buzz artists. But that means Waldoxy has to build artist name brands rather than just sell songs by older established artists.

Meanwhile, Malaco’s gospel labels under Jerry Mannery and Savoy Records under Milton Biggham earned multiple honors, including Billboard designations as Top Gospel Label and Top Gospel Distributor, while the artists received numerous awards (Grammy, Stellar, Soul Train, and Gospel Music Workshop), as well as Billboard Top Gospel Artist of the Year designations. The company also dominated Billboard Gospel charts, achieving #1 rankings by Keith Pringle, Walter Hawkins, Rev. James Moore, Mississippi Mass Choir, Rev. Clay Evans, Dorothy Norwood, and the Rev. James Cleveland.

Malaco’s market focus widened dramatically in 1995. Songwriter/producer Rich Cason cut “Good Love” on Johnnie Taylor with a contemporary L.A. jeep beat, enabling the artist to reach a new, younger audience. Combining contemporary tracks with old school material like “Last Two Dollars,” the Good Love album soared to #1 on Billboard’s blues charts and #15 R&B, becoming the biggest record in Malaco’s history.

In the late nineties, Malaco signed veteran Chicago soul great Tyrone Davis, whose credits include 42 R&B chart records. The company also continued its steady, prudent expansion, purchasing half of the Memphis-based distributor Select-O-Hits, and making inroads into the urban contemporary, jazz, and contemporary Christian markets.

The launch of Freedom Records, with contemporary Christian artists such as The Kry and Hokus Pick, evolved into Nashville-based Malaco Christian Distribution, concentrating on the growing Christian and gospel markets.

Malaco Jazz Records is issuing a series of vintage live European recordings by Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie, Lionel Hampton, Cannonball Adderly, Thelonious Monk, and others. Malaco Jazz also distributes several upcoming independent jazz labels.

And, the new urban contemporary label, J-Town, scored a Top 40 R&B single, “I’ve Been Having an Affair” by Tonya.

Even as the company continues expanding its artistic and commercial horizons, it’s a good bet that Malaco will still be the last soul company for years to come. Stay tuned!

Excerpted from The Malaco Story by Rob Bowman, award-winning author of Soulsville U.S.A.: The Story of Stax Records published by Schirmer Books.