Down Home Blues, Z.Z. Hill’s 1981–82 breakthrough smash on Malaco, hit the blues and soul music worlds like a revelation. Suddenly, in a musical marketplace dominated by post-disco mechanized pounding and the growing influence of rap and hip-hop, here was a singer whose voice sounded equal parts gravel and swamp muck. Down Home Blues delivers Hill’s dispatch from a late-night party at which his lady, slipping off her shoes and sipping a cocktail, exhorted him to “take off those fast records, and let me hear some down home blues,” while a fatback guitar chords and snakes through the mix, a fallen-angel gospel choir adds inspirational spice, and an easy-rolling blues shuffle pushes everything along with a swaggering, sensual lope.

Down Home Blues, Z.Z. Hill’s 1981–82 breakthrough smash on Malaco, hit the blues and soul music worlds like a revelation. Suddenly, in a musical marketplace dominated by post-disco mechanized pounding and the growing influence of rap and hip-hop, here was a singer whose voice sounded equal parts gravel and swamp muck. Down Home Blues delivers Hill’s dispatch from a late-night party at which his lady, slipping off her shoes and sipping a cocktail, exhorted him to “take off those fast records, and let me hear some down home blues,” while a fatback guitar chords and snakes through the mix, a fallen-angel gospel choir adds inspirational spice, and an easy-rolling blues shuffle pushes everything along with a swaggering, sensual lope.

In the wake of Hill’s hit, Malaco became a mecca for veteran soul and blues artists, most of whom had continued to record and perform steadily since their heyday but had disappeared from the charts. Bobby “Blue” Bland, Denise LaSalle, Little Milton, Johnnie Taylor, Latimore, Tyrone Davis and Shirley Brown, among others, signed within a few years after Hill’s hit. But the soul blues “revival” wasn’t just an old folks’ party; Malaco was as aggressive in attracting newer artists as it was in cultivating and nurturing time-tested veterans. Singers such as Carl Sims, Stan Mosley, Billy “Soul” Bonds, La’Keisha and Johnnie Taylor’s son Floyd (to name just a few) also came on board and found success.

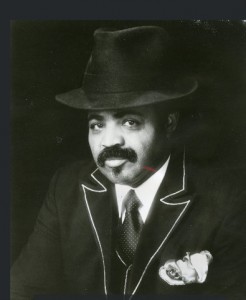

But the man who ignited this modern-day blues firestorm was no overnight sensation, no matter how unexpectedly Down Home Blues might have changed the world when it came out. Born Arzell Hill in Naples, Texas, in 1935, he sang gospel as a young man but also listened closely to blues and soul artists like Bobby Bland, B.B. King and Sam Cooke. Eventually, breaking into the local club circuit, he adopted the stage name “Z.Z.” in honor of his idol, King. In the early ’60s he did some recording for the M.H. label, owned by his brother Matt; You Were Wrong, on M.H., made the R&B charts in 1964. He followed that up with a brief stint at Mesa, after which he worked for such labels as Kent, Mankind, both Hill and Aubrey (also owned by his brother), United Artists and Columbia. Throughout the ’70s, he maintained regional celebrity through the South, and he charted a total of 14 times. His greatest success during this period was Love Is So Good When You’re Stealing It, released on Columbia in 1977.

In 1980, with the encouragement of legendary A&R man Dave Clark, he signed with Malaco, where he released Down Home Blues in November of 1981 (it became a hit the following year, appearing as the lead song on Hill’s now legendary Down Home LP). His follow-ups—Cheatin’ In the Next Room and Right Arm for Your Love (also from Down Home); Someone Else Is Steppin’ In, written by Denise LaSalle (from The Rhythm & The Blues, also in 1982); the grinding Shade Tree Mechanic (featured on 1983’s I’m a Blues Man); You’re Ruining My Bad Reputation (another LaSalle creation, this one on 1984’s Bluesmaster), among others—further codified the southern soul blues aesthetic, with Hill’s gristle-and-fatback vocals and deep-pocket rhythmic sense augmented by the roomy production and skin-tight arrangements Malaco provided him.

Although he may be best known for his humor-tinged party songs and odes to romantic misadventure, Hill was also a master balladeer. Songs like Get a Little, Give a Little and his duet with Dorothy Moore, Please Don’t Let Our Good Thing End (both from 1983’s I’m a Blues Man), seasoned with country plaintiveness but soul-charged and churchy in the great tradition, are among the most heart-rending in all of contemporary soul blues. Hill, who suffered a heart attack and died in Dallas on April 27, 1984, released five albums on Malaco, beginning with his eponymous 1981 debut. Two posthumous tribute/compilations—In Memoriam (1935–1984), issued in 1985, and Greatest Hits from 1990—are also available. In Z.Z. Hill’s music, you can hear the precise nexus where blues and soul tradition meet soul blues innovation—a point of encounter as thrilling to experience now as it was then.

—David Whiteis

Buy from:

Buy from:  Buy from:

Buy from:  Buy from:

Buy from:  Buy from:

Buy from:  Buy from:

Buy from:  Buy from:

Buy from:  Buy from:

Buy from:  Buy from:

Buy from:  Buy from:

Buy from: